Human Digestive System Parts and Functions

The digestive system, comprised of key parts, efficiently breaks down food for nutrient absorption, featuring organs like the mouth, stomach, and intestines․

The human digestive system is a complex and fascinating network responsible for breaking down food, absorbing vital nutrients, and eliminating waste․ This intricate process begins in the mouth and continues through a series of organs, collectively known as the gastrointestinal tract․

Understanding its parts and functions is crucial for maintaining overall health․ From the initial mechanical breakdown by teeth to the chemical digestion aided by enzymes, each stage plays a vital role․ Accessory organs, like the liver and pancreas, contribute significantly by producing essential substances for digestion․

This system ensures the body receives the energy and building blocks needed to thrive․

Overview of the Gastrointestinal Tract

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract forms a continuous pathway, extending from the mouth to the anus, facilitating food processing․ This remarkable tube includes the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine, each uniquely adapted for specific digestive tasks․

Food travels through these organs via coordinated muscular contractions called peristalsis․ The GI tract’s primary function is to dismantle food into smaller molecules the body can absorb․

Its efficient operation relies on the interplay of mechanical actions, chemical digestion, and the contributions of accessory digestive organs, ensuring optimal nutrient uptake and waste removal․

Key Organs Involved in Digestion

Essential organs orchestrate the digestive process, beginning with the mouth, where mechanical and chemical breakdown initiates․ The esophagus transports food to the stomach, a crucial site for acid-mediated digestion and initial protein breakdown․

The small intestine is paramount for nutrient absorption, aided by the pancreas and liver, providing enzymes and bile respectively․ Finally, the large intestine absorbs water and forms feces for elimination․

These organs, working in harmony, ensure efficient nutrient extraction and waste management․

The Mouth and Initial Breakdown

The mouth initiates digestion through teeth and salivary glands, mechanically breaking down food and beginning chemical digestion with enzymes․

Role of Salivary Glands

Salivary glands are crucial accessory organs, initiating the digestive process within the oral cavity․ These glands produce saliva, a complex fluid containing water, electrolytes, mucus, and vital digestive enzymes, most notably amylase․ Amylase begins the breakdown of carbohydrates, specifically starches, into simpler sugars․

Saliva also lubricates food, facilitating the formation of a bolus – a cohesive mass ready for swallowing․ Furthermore, saliva possesses antibacterial properties, helping to cleanse the mouth and protect against microbial infections․ Mucus within saliva aids in binding food particles, easing their passage through the digestive tract․ The production of saliva is regulated by the nervous system, responding to stimuli like the sight, smell, or thought of food․

Teeth and Mechanical Digestion

Teeth play a fundamental role in mechanical digestion, physically breaking down food into smaller particles․ This process increases the surface area available for enzymatic action, enhancing the efficiency of chemical digestion․ Different types of teeth – incisors, canines, premolars, and molars – are specialized for various functions, including cutting, tearing, and grinding food․

The enamel coating protects teeth from wear and tear during this rigorous process․ Jaw muscles facilitate the movements necessary for chewing, creating a forceful grinding action․ Effective mechanical digestion is essential for proper nutrient absorption and prevents strain on subsequent digestive organs․

Tongue and Bolus Formation

The tongue is a muscular organ crucial for both taste and the manipulation of food within the mouth․ It mixes food with saliva, initiating chemical digestion, and importantly, forms the bolus – a rounded mass of chewed food․ This bolus is then propelled towards the pharynx for swallowing․

The tongue’s surface contains papillae, housing taste buds․ Its movements assist in positioning food between the teeth for efficient grinding․ Furthermore, the tongue aids in speech and helps clear the mouth of residual food particles, contributing to overall oral hygiene and preparing for the next stage of digestion․

Esophagus and Swallowing

The esophagus transports food from the mouth to the stomach via coordinated muscle contractions, initiating the swallowing process for efficient digestion․

Peristalsis and Food Transport

Peristalsis is a crucial wave-like muscular contraction that propels food along the gastrointestinal tract, beginning in the esophagus․ This involuntary process ensures one-way movement, preventing backflow and efficiently transporting the bolus – the chewed food mass – towards the stomach․ The esophageal muscles rhythmically contract and relax, squeezing the food downwards․

This coordinated action isn’t simply pushing; it involves complex neural control and ensures food progresses even against gravity․ The strength and speed of peristalsis adjust based on food volume and consistency, optimizing transport․ Without peristalsis, digestion would be severely impaired, hindering nutrient absorption and overall health․ It’s a fundamental mechanism for effective food delivery․

Stomach: A Major Digestive Hub

The stomach serves as a central digestive site, utilizing gastric juices and muscular churning to break down food, particularly initiating protein digestion․

Gastric Juices and Acidic Environment

Gastric juices, a complex mixture secreted by the stomach lining, are crucial for initiating protein breakdown and eliminating harmful bacteria․ These juices contain hydrochloric acid (HCl), creating a highly acidic environment – a pH between 1․5 and 3․5 – essential for activating pepsin, the primary enzyme responsible for protein digestion․

This acidity also helps to denature proteins, unfolding their complex structures to make them more accessible to enzymatic attack․ Mucus secreted by the stomach lining protects the stomach wall from the corrosive effects of the acid․ The interplay between acid, enzymes, and mucus ensures efficient digestion while safeguarding the stomach itself․

Churning and Mixing of Food

The stomach doesn’t just passively hold food; it actively churns and mixes it with gastric juices․ This mechanical digestion is achieved through strong muscular contractions of the stomach walls․ These contractions break down food into smaller particles, increasing the surface area available for enzymatic action․

This mixing process also ensures that food is thoroughly combined with gastric secretions, creating a semi-liquid mixture called chyme․ The churning action continues for several hours, gradually releasing chyme into the small intestine for further processing․ This efficient mixing is vital for optimal digestion and nutrient absorption․

Role of the Stomach in Protein Digestion

The stomach plays a crucial role in initiating protein digestion․ Chief cells within the stomach lining secrete pepsinogen, an inactive enzyme․ Hydrochloric acid (HCl), produced by parietal cells, converts pepsinogen into its active form, pepsin․

Pepsin begins the breakdown of proteins into smaller polypeptide chains․ This process is essential as proteins are complex molecules requiring significant breakdown for absorption․ While the stomach doesn’t complete protein digestion, it significantly prepares proteins for further enzymatic action in the small intestine, maximizing nutrient availability․

Small Intestine: Nutrient Absorption

The small intestine—duodenum, jejunum, and ileum—is the primary site for nutrient absorption, utilizing villi and microvilli to maximize surface area․

Duodenum, Jejunum, and Ileum

The small intestine is remarkably divided into three distinct segments: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, each playing a crucial role in the digestive and absorptive processes․ The duodenum, the shortest section, receives chyme from the stomach and digestive secretions from the pancreas and liver․

The jejunum follows, responsible for a significant portion of nutrient absorption due to its extensive villi and microvilli․ Finally, the ileum absorbs vitamin B12, bile salts, and any remaining nutrients, connecting to the large intestine․ These segments work in concert to ensure efficient digestion and nutrient uptake․

Villi and Microvilli for Increased Surface Area

The small intestine’s remarkable absorptive capacity is largely due to its unique structural features: villi and microvilli․ Villi are tiny, finger-like projections lining the intestinal wall, dramatically increasing the surface area available for nutrient absorption․

Each villus is further covered in even smaller projections called microvilli, forming a “brush border” that exponentially expands the absorptive surface․ This extensive surface area maximizes contact between digested food and the intestinal lining, facilitating efficient uptake of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats into the bloodstream․

Absorption of Carbohydrates, Proteins, and Fats

The small intestine is the primary site for nutrient absorption, expertly handling carbohydrates, proteins, and fats․ Carbohydrates, broken down into simple sugars, are absorbed via active transport and facilitated diffusion․ Proteins, reduced to amino acids, utilize similar transport mechanisms․

Fats, emulsified by bile, are absorbed into lacteals – lymphatic vessels within the villi – before entering the bloodstream․ This efficient absorption process ensures the body receives essential building blocks and energy sources from the food we consume, sustaining vital functions․

Large Intestine: Water Absorption and Waste Elimination

The large intestine absorbs water from undigested material, forming feces, which are then stored in the rectum before elimination through the anus․

Cecum, Colon, and Rectum

The cecum, a pouch at the large intestine’s start, connects to the ileum and initiates compaction․ The colon, extending from the cecum, absorbs water and electrolytes, solidifying waste․ It’s divided into ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid sections․

The rectum serves as a temporary storage site for feces before elimination․ Its muscular walls expand to accommodate waste, triggering the urge to defecate․ These interconnected structures efficiently process undigested material, reclaiming vital resources and preparing waste for removal from the body, completing a crucial stage in digestive function․

Formation and Storage of Feces

Feces formation begins in the large intestine, where water absorption concentrates undigested materials – fiber, bacteria, and cellular debris․ Peristaltic contractions propel this waste towards the rectum․ Storage within the rectum is facilitated by its expandable walls, accommodating accumulating fecal matter․

This process is crucial for efficient waste management․ The rectum signals the need for elimination when full, initiating the defecation reflex․ Proper fecal consistency and storage are vital for regular bowel movements and overall digestive health, ensuring the body effectively removes unusable substances․

Accessory Organs of Digestion

Accessory structures, including salivary glands, the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas, aid digestion by producing enzymes and bile, supporting the gastrointestinal tract․

Liver and Bile Production

The liver plays a crucial role in digestion by producing bile, a fluid essential for fat emulsification and absorption within the small intestine․ This process breaks down fats into smaller globules, increasing their surface area for enzymatic action․ Bile also aids in the elimination of waste products from the body․

Beyond bile production, the liver performs numerous other vital functions, including nutrient processing, detoxification, and storage of glycogen․ It receives blood from the digestive tract, processing absorbed nutrients before distributing them to the rest of the body․ Its multifaceted role makes it indispensable for overall digestive health and metabolic balance․

Gallbladder and Bile Storage

The gallbladder serves as a storage reservoir for bile produced by the liver․ When fat enters the duodenum, the gallbladder contracts, releasing bile into the small intestine to aid in digestion and absorption․ This concentrated bile efficiently emulsifies fats, facilitating their breakdown by pancreatic lipases․

Between meals, the gallbladder concentrates and stores bile, optimizing its availability when needed․ Issues with the gallbladder, such as gallstones, can disrupt this process, leading to digestive discomfort․ Its strategic function ensures a readily available supply of bile for effective fat digestion․

Pancreas and Digestive Enzymes

The pancreas plays a crucial dual role, functioning as both an endocrine and exocrine gland․ Its exocrine function is vital for digestion, producing potent digestive enzymes like amylase, protease, and lipase․ These enzymes are secreted into the duodenum to break down carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, respectively․

The pancreas also produces bicarbonate, neutralizing acidic chyme entering from the stomach, creating an optimal pH for enzyme activity․ Proper pancreatic function is essential for efficient nutrient absorption, and disruptions can lead to maldigestion and related health issues․

Digestive Enzymes and Their Functions

Amylase, protease, and lipase are key enzymes; amylase digests carbohydrates, protease breaks down proteins, and lipase tackles fats for absorption․

Amylase, Protease, and Lipase

Amylase, primarily produced in the salivary glands and pancreas, initiates carbohydrate digestion by breaking down starches into simpler sugars like glucose․ Protease, including pepsin in the stomach and trypsin/chymotrypsin in the small intestine, dismantles proteins into amino acids, essential for building and repairing tissues․

Lipase, secreted by the pancreas, is crucial for fat digestion, converting triglycerides into fatty acids and glycerol, which are then absorbed․ These enzymes work synergistically, ensuring efficient nutrient extraction․ Their activity is highly regulated, influenced by factors like pH and the presence of co-enzymes, optimizing the digestive process throughout the gastrointestinal tract․

The Digestive Process: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

Digestion involves four key stages: ingestion, digestion, absorption, and elimination, working sequentially to process food and extract vital nutrients for bodily functions․

Ingestion, Digestion, Absorption, and Elimination

Ingestion marks the start, introducing food into the system via the mouth․ Digestion then breaks down food—both mechanically and chemically—into smaller molecules․ This process utilizes gastric juices and enzymes throughout the gastrointestinal tract․

Next, absorption occurs primarily in the small intestine, where nutrients pass into the bloodstream for distribution․ The villi and microvilli maximize surface area for efficient uptake․ Finally, elimination removes indigestible waste materials through the large intestine and rectum, completing the digestive cycle․ These coordinated steps ensure proper nutrient utilization․

Age-Related Changes in the Digestive System

Aging impacts digestive functions, potentially increasing susceptibility to gastrointestinal conditions due to alterations in the system’s efficiency and overall performance․

Impact of Aging on Digestive Function

As individuals age, noticeable changes occur within the digestive system, impacting its overall functionality․ These alterations can manifest as reduced production of gastric juices, potentially hindering protein digestion and nutrient absorption․ Peristalsis, the muscular contractions propelling food through the gastrointestinal tract, may also slow down, leading to constipation and discomfort․

Furthermore, the structural integrity of the digestive organs can diminish with age, affecting their ability to efficiently process food․ The decline in enzyme production further complicates the digestive process․ Consequently, older adults may experience increased sensitivity to certain foods and a greater predisposition to gastrointestinal disorders, necessitating dietary adjustments and attentive healthcare․

Common Digestive Disorders

Gastrointestinal conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome and acid reflux, frequently disrupt digestive processes, impacting the system’s ability to function optimally․

Overview of Gastrointestinal Conditions

Gastrointestinal (GI) conditions encompass a wide spectrum of disorders affecting the digestive system․ These range from common ailments like heartburn and indigestion to more serious diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis․ Factors contributing to these conditions include diet, stress, infections, and genetic predispositions․

Symptoms can vary greatly, including abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and vomiting․ Accurate diagnosis often requires a combination of physical examinations, imaging tests, and endoscopic procedures․ Management strategies depend on the specific condition and severity, potentially involving lifestyle modifications, medication, or even surgical intervention․ Early detection and appropriate treatment are crucial for improving quality of life․

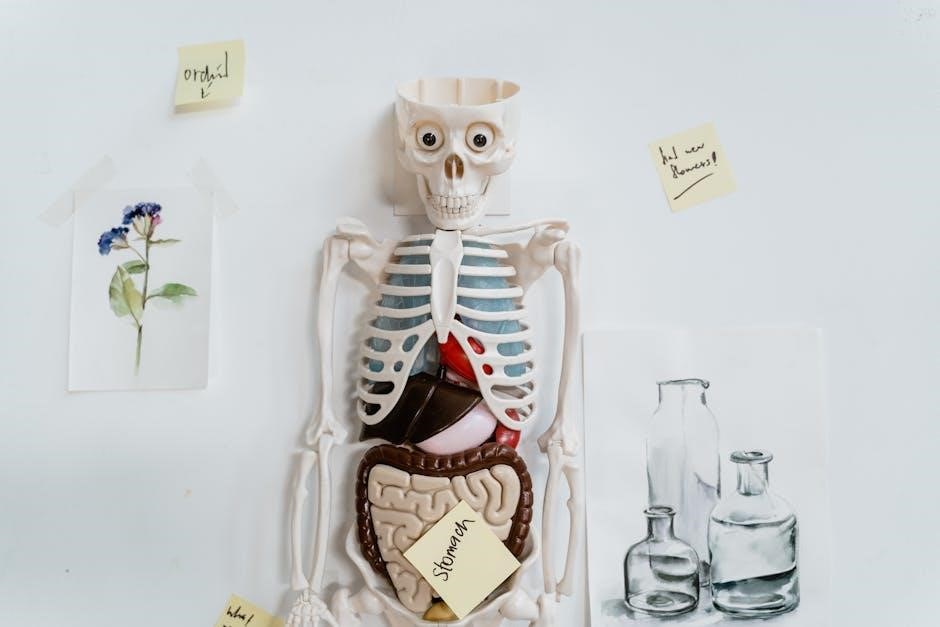

Diagram of the Human Digestive System

Labeled illustrations depict the digestive organs – mouth, esophagus, stomach, intestines, liver, pancreas – showcasing the pathway of food and nutrient absorption․

Labeled Illustration of Digestive Organs

Detailed diagrams visually represent the human digestive system’s components, including the mouth, esophagus, stomach, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, small and large intestines, rectum, and associated glands․ These illustrations pinpoint each organ’s location and its specific role in the digestive process․

Key features highlighted are the stomach’s churning action, the small intestine’s villi for nutrient absorption, and the large intestine’s water absorption function․ The liver and pancreas are shown contributing essential digestive juices․ Such visual aids enhance understanding of how food travels and is processed, ultimately supporting overall health and well-being․

PDF Resources for Further Study

Educational PDFs offer in-depth exploration of the human digestive system, detailing organ functions and processes for comprehensive learning and research․

Links to Educational Materials

Delve deeper into understanding the human digestive system with these valuable online resources․ Numerous PDF documents provide detailed diagrams and explanations of each organ’s function, from the initial breakdown in the mouth to waste elimination․ Explore interactive models showcasing peristalsis and nutrient absorption within the small intestine․ Access comprehensive guides covering gastric juices, enzyme roles, and the interplay of accessory organs like the liver and pancreas․

These materials are ideal for students, educators, and anyone seeking a thorough grasp of this vital biological system․ Discover downloadable infographics illustrating the entire digestive process, step-by-step, enhancing your comprehension․